My Research

The canyons in the Channeled Scabland of Eastern Washington were carved when floods from the ice-dammed glacial Lake Missoula eroded columns of basalt during the last Ice Age. The extent of erosion, and position of since-retreated glaciers, dictated how much water could flow along that route. These three models show how vastly different amounts of water can reach the same spot on the landscape when we change the boundary conditions to represent different phases of the canyon’s evolution.

So which one is right? We sample flood-transported granite boulders to sort out the timing of floods on different surfaces and along different pathways. When something sits on the Earth’s surface for a long time, it accumulates an isotope called beryllium-10 at a predictable rate from cosmic rays. We can measure the amount of beryllium-10 in a rock, and use it as a clock to say when that rock was eroded, transported, and deposited by floods. Explore our sample locations throughout the Scablands here!

We can also test whether floods of different sizes would be big enough to erode the rock that makes up the landscape. The Channeled Scablands are a neat place to test this because the columnar basalt that makes up the bedrock has a relatively consistent fracture geometry, and the straight walls of canyons like Grand Coulee indicate that they were probably carved by giant waterfalls that retreated as they eroded.

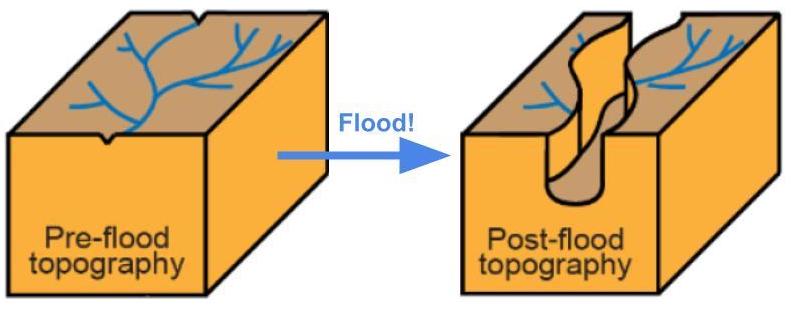

Another big question is: what did the landscape look like before it was altered by erosion from big floods? If we want to model floods on topography similar to what they would have encountered, rather than the modern landscape, we need to make some assumptions about what that prior landscape looked like--which is hard to do when it’s gone! Luckily, many landscapes contain clues to help us reconstruct prior land surfaces over which we can run our hydraulic models of early floods.

In the Channeled Scablands, we use hanging tributaries to interpolate a pre-incision valley. In northern Norway, the canyon is so narrow we can just connect the banks. On Mars, terraces from successive waves of incision tell us the elevation of the channel floor at different times.